How Children Learn To Read

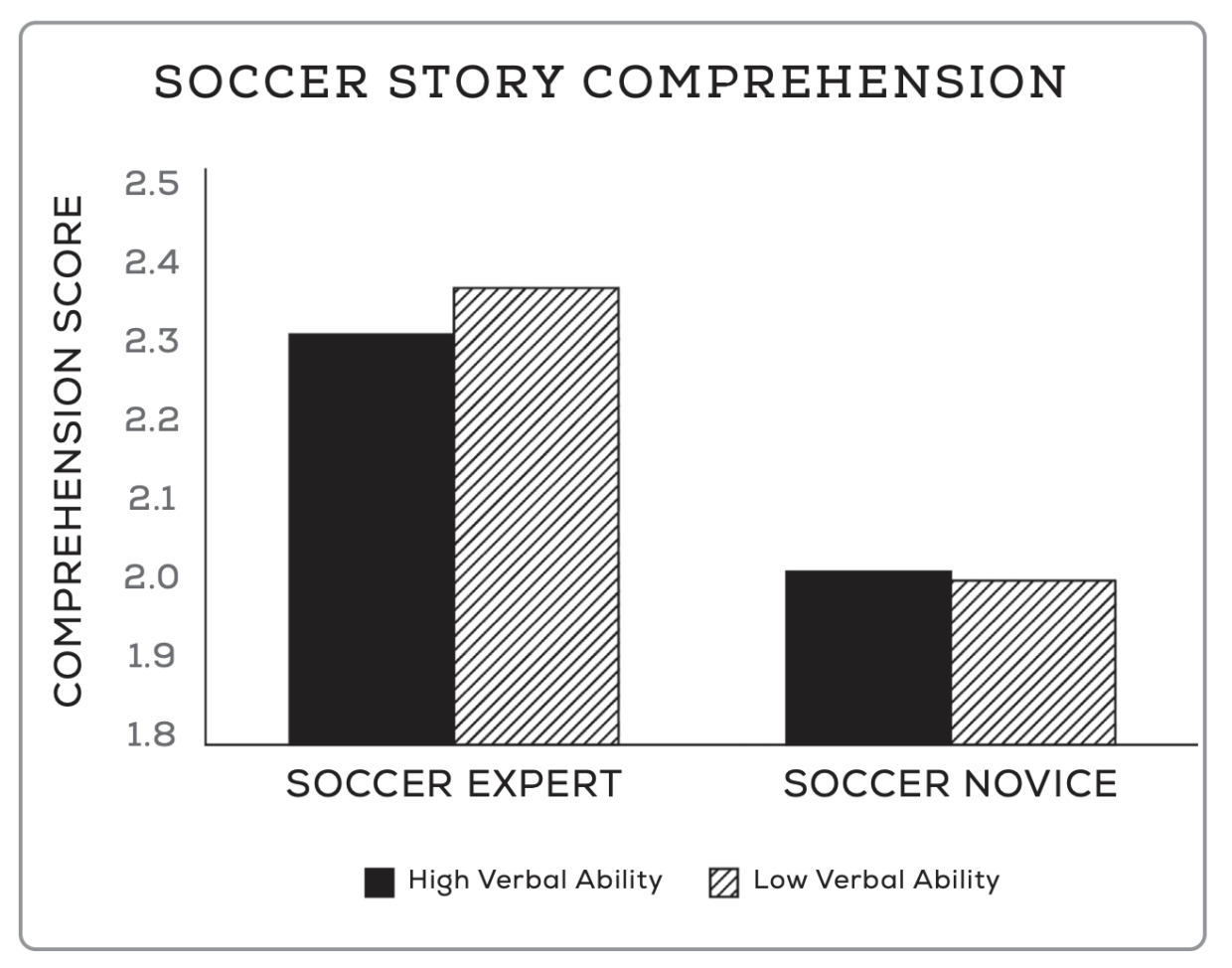

Amid my favorite book genres is histories of 19th‑century polar expeditions (spoiler alert: information technology's super, super cold and a lot of people die). My married man, Jesse, and I share many interests, but not this one. The terminal time I read one of these books and tried to tell him what was happening, he retaliated by explaining the details of the book he was reading, which was—I'yard totally not making this upwardly—a history of the German Federal Statistical Function. Simply for me, a close second to books on polar explorers are books on neuroscience, which is where I call back it makes sense to commencement in understanding the question of how kids learn to read. Because before thinking about how kids learn to read, it is useful to call back about how adults (or fluent readers in general) actually read. Of particular relevance is the question of whether you lot read by recognizing words or by sounding them out. If y'all're a fluent adult reader, you probably think that you lot read by recognizing words and just knowing what they look similar. Basically, you perceive yourself using some kind of pattern recognition—when you encounter the give-and-take read, yous recognize it as "read." You lot do not think of yourself as sounding it out. And for a word like read, this is likely correct. For short, common words, we seem to read through pattern recognition. (How do nosotros know this? 1 piece of show is that for short words—say, under viii characters—the length of the word doesn't influence our reading speed. If we were sounding it out, this wouldn't be the instance. Other bear witness comes from brain scans that expect at how the brain processes real versus imaginary words.) But it turns out that although you lot exercise non perceive it, y'all really besides make use of a fair amount of phonics (basically, chunking words and sounding them out) inside your encephalon when reading. You do it fast! Just that doesn't mean y'all don't practise it. And it'southward the reason we tin procedure words nosotros haven't seen before, or imaginary words. For example, here's a word I made up: delumpification. You tin can likely read this, in the sense that you could pronounce it. And beyond that, you probably tin piece of work out what information technology would hateful (something similar, "the process of removing a lump"). Simply this isn't because you recognize the word! Implicitly, your brain is sounding it out in pieces it knows: de / lump / ifi cation (perhaps—our exact noesis nearly how this blazon of word gets chunked isn't perfect). Agreement this procedure, and in item understanding the sense in which even fluent readers rely on sounding out to read, has implications for how kids larn to read. Notably, it is key to the great debate over teaching phonics versus "whole linguistic communication" reading. Traditionally, reading has been taught through the utilise of phonics—kids acquire the sounds of letters, and so how they fit together (the consonant‑vowel‑consonant words), so common exceptions ("if there is an due east at the end, a says its ain name"; "ou" says "oww," etc.), then weirder things (the silent yard and so on). If yous're familiar with them, think of the Bob Books. They start with just four messages (a, yard, south, and t) and the first book in its entirety is: "Mat, Mat sat, Sam, Sam sabbatum, Mat saturday on Sam, Sam sat on Mat, Mat sabbatum, Sam sabbatum." The next book introduces more letters (c, d), so on. Phonics has been used (successfully) for decades, probably hundreds of years. But at some point, some people suggested it might non be the best approach. Beginning in the late 1960s, a movement (credited to, amid others, linguist Noam Chomsky) suggested that it might be better to teach reading with a more "whole‑linguistic communication" approach. In particular, this move argued for forgetting about phonics and immersing children in linguistic communication and stories with the expectation that they would, effectively, learn pattern recognition to read words. To simplify somewhat, in that location were a couple of arguments in favor of this. One is that phonics is boring. That "Mat" story from the Bob Books? No five‑ or six‑yr‑old volition find it exciting. It's a chore. Similarly, drilling on the millions of exceptions in the English linguistic communication is tedious. Why on world is the k silent? A whole‑language approach skips correct to ameliorate stories—not Harry Potter, but at least something that's not quite so pedantic. So maybe information technology holds kids' interest better. The other point this movement made is that when adults read, they read through pattern recognition, and if that'southward where kids are headed anyway, nosotros might besides start there. The whole‑language approach got some traction in the 80s and 90s; at some betoken, California public schools adopted a version of it, equally did Massachusetts. As information technology turns out, however, ignoring phonics is not an appropriate way to teach reading. For one thing, as mentioned before, adults reading past pattern recognition lone is wrong. Fifty-fifty fluent readers are using a form of sounding out to read many words. And so chunking words and putting them back together is a cardinal tool. This suggests that we ignore it at our peril. Only we can also see the failure of this whole‑linguistic communication arroyo in experimental data. A team of researchers at Stanford showed this in a clever experiment in which they invented a new script and attempted to teach it to undergraduates. The script had English audio correspondence, but the letters looked different. Some undergraduates were encouraged to learn using a phonics frame (basically, to work out which squiggle corresponded to which sound) and others were encouraged to utilise a whole‑word approach (memorizing which pic corresponded to which give-and-take). The students using the whole‑word approach initially did better, but once more than words were added, they were unable to keep upwards; phonics facilitated the reading of a larger number of words with a smaller number of symbols. A big number of studies show that phonics‑based reading instruction is more successful than whole‑language reading. Some people have even argued that the California adoption of this whole‑language approach was responsible for a precipitous refuse in exam scores in California in the 80s and 90s, although this is subject to some debate. In the finish, phonics has returned, and this is almost certainly what your kid'due south school will use. (It's besides probably how you should teach them to read, if you choose to do it yourself.) If you find that your child's school has adopted a whole‑language approach, y'all should inquire a lot of questions. At that place is some button for what people phone call "balanced literacy," meaning that basic phonics instruction is combined with more interesting story reading. This adopts some of what is "fun" about the whole‑language approach—you can rapidly movement beyond the Bob Books—but the main focus stays on phonics as the central learning tool. And so, when will this all happen? When is your kid actually going to larn to read? If yous want to pitch reading as entertainment, you need to be prepared to let them pick what they want. I talked some in Cribsheet about reading amid very immature children. Yous tin can certainly find products that tell yous your baby can learn to read. They can't! Science has proven it. Please, please do not try to teach your baby to read (it will frustrate and disappoint you, they probably will not like it, and it volition non work). Toddlers and preschoolers also (in most cases) cannot read fluently. Kids of 2 and 3 years old volition often start doing some blueprint recognition—recognizing their name, or the M in the McDonald's arches, or a particular logo. This is great, and it's smashing to encourage information technology! Simply it's not reading. Some very young children practice learn to read fluently, but it's unusual. With an older 3‑ or four‑year‑old, you may exist able to commencement doing some early phonics, and certainly a four‑year‑old tin can understand the idea of messages. This may especially be truthful if they accept an older sibling who is learning to read. (One thing to notation here is that there is often a lot of focus on learning the names of the messages, but this is actually far less important for reading than the letter sounds.) Most kids learn to read—to put letters together into words and read somewhat fluently—sometime between first and 3rd course. We can see this in data. The following graph shows the development of reading skills based on information from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Written report, a written report that tracked a cohort of students who were in kindergarten in 1998. Students in this cohort were evaluated on their reading skills in kindergarten, offset grade, 3rd grade, 5th grade, and eighth grade. At each fourth dimension period, they got a score that indicated their proficiency at each reading skill. These skills start at letter recognition and go all the fashion up to evaluating the students' comprehension of complex nonfiction texts. I focus here on the evolution of students' reading abilities early on in their school career—from kindergarten through the end of third course. When the kids entered kindergarten in the fall, most of them (about 70 percent) could recognize letters, simply merely a pocket-sized share (about 30 percent) could recognize starting time sounds of words. Nearly none of them could recognize sight words or comprehend words in context (this last milestone would be shut to reading uncomplicated texts). By the beginning of first class, letter recognition and get-go‑sound recognition had advanced, but nevertheless only a small share of kids could recognize sight words or actually read texts. This skill enormously advanced during first course. By the spring of that year, 80 percentage of the accomplice could recognize sight words and nigh half could read in context. By the finish of third grade, about the whole cohort was reading fluently, although still only nearly a quarter of them were comprehending texts at a loftier level. This skill comes subsequently in the data, toward the finish of fifth form and especially by 8th grade. Note that this varies a bit across languages. English is harder to read than a linguistic communication like Castilian or Italian, since the latter have finer complete letter‑to‑sound correspondence, whereas English has a lot of spelling exceptions. As a upshot, Spanish and Italian speakers acquire to read faster. Languages with characters rather than letters (like some East Asian languages) are much harder—they require more of the whole‑linguistic communication arroyo by definition—and accept much longer to read fluently. Based on the data in the previous graph, we see that by the tertiary grade about all the children can read somewhat fluently, and a good share are starting to be able to better understand what they read—to motility from "learning to read" to "reading to learn." And so the question becomes: Can you get them to like it? Much ink has been spilled on the question of how to get your kids to like to read. An Amazon perusal reveals plenty of volume‑length takes—Raising Kids Who Love to Read, Resistant to Reading: Tips and Tricks, How to Get Your Screen-Loving Kids to Read for Pleasance, and then on. To a big extent, these books focus on a category of kids they label "reluctant readers"— basically, kids who aren't really into reading for fun. Kids can be reluctant readers at whatsoever age, but it's also worth noting that as kids age, they tend to read less for pleasance. It's not that surprising—as more time is scheduled for homework and activities and kids get more access to technology, reading may take a dorsum seat. The books dedicated to this issue have 2 key letters. First, if y'all desire to encourage your kids to read for pleasure, it helps to explicitly make time for this. Y'all may want to say, for example, "Our family is going to take this 45‑infinitesimal block on a weekend afternoon to all read together." Generally, the idea would exist to pitch this as "free" reading time—y'all can read annihilation you want: catalogs, baby books, a serious novel, any. It's not a punishment, it's a course of entertainment. Like family picture show night, simply with books. There are diverse obvious times to practise this—before bed, gratis fourth dimension on weekends, early morning before it's wake‑up time. My kids do a lot of their reading at breakfast (our family dominion is you tin can read at breakfast and lunch but not dinner, which makes information technology seem like a treat). Every bit yous think about this, though, you do want to go back to the family Big Movie. Devoting the pre‑bedtime catamenia to reading could crowd out other things—other family time, extracurriculars, sleep, family dinner. And once more, having your kid honey to read may or may not be super of import to you. So be deliberate! The 2d key (and possibly blindingly obvious) message of these books is that kids like reading meliorate if they are adept at it and if they understand what they are reading. Closely related to this is the observation that understanding the context of what you're reading is extremely important for absorbing it. One nice study demonstrating this was published in 1989 in the Jour nal of Educational Psychology. The authors took a prepare of elementary schoolers in Deutschland and tested their comprehension of a story about soccer; the story was provided both in audiobook and written class, and then this was actually a test of their verbal comprehension abilities, not reading specifically. The authors categorized the children in two ways before the test. First, they used a generic verbal IQ test to classify the kids equally high or low bent on verbal skills, including general comprehension and vocabulary. Second, they used a multiple‑choice quiz to assess the students' knowledge about soccer; they classified the students as either experts or novices on the topic of soccer. What the authors found—see one of their results in the higher up graph—was that comprehension of the story (measured in a large number of ways) was much amend for those kids who were soccer experts, and this upshot swamped any effect of full general exact aptitude. Basically, the kids with low verbal power who knew a lot about soccer got a lot more out of the story than those with high exact ability who did not know much about soccer. Contextual agreement is hugely of import for reading comprehension. And, past extension, for enjoying reading. If your kid has no interest in polar bears and no noesis of polar bears, they are probably not going to enjoy reading a dumbo scientific treatise about polar bears. And non every kid has the same ready of interests. Various studies have shown that when kids are given a chance to choose what they read, information technology improves their interest in reading. There are a big number of (mostly school‑based) interventions designed to encourage kids to read. The exact methods vary, but they tend to share the feature that they let kids choose the books they want to read and and so encourage kids to talk near the books (thus providing more content and engagement). Flexibility in reading option is actually important. Yes, your kid is likely to have to read certain books for school—that's inevitable and probably proficient for them. But if y'all want to pitch reading equally entertainment, to have a "family reading time" or bedtime reading—you need to exist prepared to permit them pick what they want. You may accept loved A Contraction in Time as a kid, merely you shouldn't force information technology downwards your child's throat if they'd rather read The Country of Stories. Some good share of the time, your kid is probably going to choice books that are below their maximum reading level. This is likewise okay. Amusement reading time is not for pushing oneself to the maximum. You yourself are probably not going to read James Joyce for recreation. Finally, this likely calls for some flexibility in book genre. Increasingly people are recognizing the value of graphic novels for engaging both reluctant and happy readers. For a couple of weeks in the autumn of 2019, the bestselling volume overall in the Us was a graphic novel chosen Guts by the absolutely awesome Raina Telgemeier. Okay, so it has pictures. Simply it's still reading. A like point can be made for intermediate books like the Diary of a Wimpy Child, Dog Man, and—I hesitate to mention—the Captain Underpants series. No matter what you practise, even with dedicated reading time and book pick, some kids just like reading amend than others. This is as well true of adults. This is perhaps one of the many times in parenting we should pace back and recall that our kids are their own people and some things are out of our control. It is a hard lesson. _________________________________ From The Family Firm: A Data-Driven Guide to Improve Decision Making in the Early on School Years by Emily Oster, to be published by Penguin Press, an banner of Penguin Publishing Grouping, a division of Penguin Random Business firm, LLC. Copyright © 2021 past Emily Oster.

Source: https://lithub.com/what-the-data-says-about-how-kids-learn-to-read-and-learn-to-like-it/

Posted by: reedythrome.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Children Learn To Read"

Post a Comment